SEE ALL THE PHOTOS ON OUR FLICKR PAGE

Clybourne Park is a play that smiles politely while it tightens the screws, and Riverside Community Players’ current production understands that the danger of Bruce Norris’s script is not in its volume, but in its familiarity. Set in the same house across two eras, the play asks the audience to sit with the uncomfortable realization that while language evolves, power often does not.

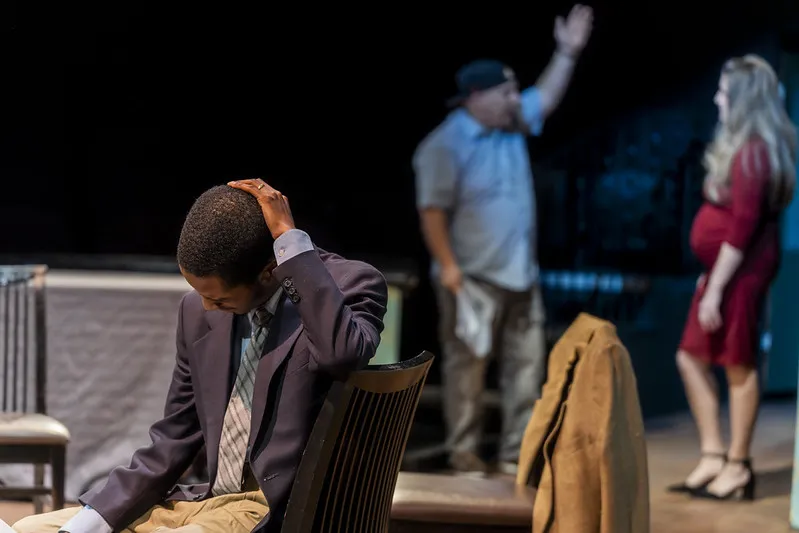

Act One unfolds with a deceptively gentle rhythm. Neighbors arrive, pleasantries are exchanged, and concern is expressed in tones so careful they practically come with lace doilies. At the center of this is Russ, played by Mark Anthony Flynn, whose performance grounds the act with a simmering frustration that bubbles and bubbles until it explodes. Flynn captures a man exhausted by grief and intrusion, someone who wants nothing more than to be left alone, and whose anger feels cumulative rather than reactive. Flynn's performance comes through perfectly allowing the audience to live in that moment where you want to drop the pretense and tell people where they should go.

Across from him, Jamie Kaufman’s Bev radiates manic cheer, the kind of relentless politeness that becomes unsettling through sheer persistence. Kaufman plays Bev as a pressure cooker disguised as a hostess, simmering with small talk and well-meaning intrusions that reveal a deeply ingrained need to be seen as good. Her white savior instincts are never cartoonish. They emerge naturally, which makes them harder to dismiss.

Then there is Karl, played by Jarod East, who earns his role as the audience’s most punchable presence. East’s performance is infuriating in precisely the right way. Karl’s entitlement is delivered with smug sincerity, the kind of casual cruelty that does not think of itself as cruel at all, and just can't understand why you're annoyed. The impulse to recoil from him is the brilliance his performance brings to the stage and is doing exactly what it should.

Act One shows the casual and polite racism that embodied "White Flight" in the 50's and then Act Two brings it around full circle to show how fifty-years later nothing has changed, but gentrification brings the casual racism back to the neighborhood with a side of "White Saviourism." The same house hosts a different set of characters debating redevelopment and preservation, and the production’s use of doubling becomes its sharpest weapon. Arguments repeat. Physical boundaries are tested in mirrored ways. Reactions to touch echo across time. Seeing the same actors occupy flipped social positions makes the play’s point not intellectually, but viscerally.

East’s transformation into Steve in Act Two is particularly effective. As Steve, he becomes the casually racist professional who is utterly and intentionally oblivious to the harm of what he is saying. The performance never tips into parody. Steve knows which lines he's not allowed to cross, but loves to dance along the line in the guise of "it's just a joke." He is familiar, which makes his statements and the reactions of those around him more damning than overt hostility ever could.

It would be a mistake not to highlight the work of Torrione Hodge and Emonnie Essence, who carry enormous weight across both timelines. As Black characters navigating casual racism in different historical moments, they are given fewer lines than their white counterparts, yet Hodge and Emonnie communicate volumes through posture, timing, and expression. Their tired, restrained reactions speak as loudly as any monologue. In the confrontation with Steve, the tension crackles not because of raised voices, but because of who is expected to absorb discomfort and who is allowed to create it. Their performances make that imbalance unmistakable.

Director Cindi East spoke before the show about why Clybourne Park remains urgent. She described the play as one that “imagines the events that unfolded in, before, and after Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 play, A Raisin in the Sun,” noting that it addresses “issues of race, class, and gender.”

She emphasized that time has not resolved the tensions at the heart of the story. “The play examines how conversations around these issues have and have not changed over fifty years, often using humor,” East said.

East pointed to recurring themes that resonate strongly today, including “white flight, racism disguised as community concern, grief, ableism, otherism, and the inability to escape past prejudices,” alongside gentrification and “the struggle to have honest conversations about race.”

“These all are issues and circumstances that are close to my heart,” she said. “I feel them deeply. They are as relevant now as they have always been.”

Acknowledging the demands the play places on performers, East added, “While the dialogue and action in this play is rough and difficult for our actors to convey, they are exceptional in their portrayal of these flawed characters.”

Her hope for the audience is direct. “As the audience leaves the arena,” East said, “they reflect on the climate of today and vow to make a difference.”

This is not a comfortable play, nor should it be. Riverside Community Players deliver a production that trusts the text, embraces its discomfort, and allows the echoes between past and present to do their unsettling work.

Clybourne Park runs January 30 through February 15, 2026, at Riverside Community Players, located at 4026 14th Street in Riverside. Tickets can be purchased online at riversidecommunityplayers.com or by calling the box office at 951-686-4030.